Tucked between the bustling economic hub of Shinjuku lies the “little Korea” of Japan. A quick train ride and a short walk are all it takes to enter Shin-Ōkubo, Tokyo’s convenient gateway to Korean culture. This cultural intersection of Japan and Korea offers visitors a momentary escape from their daily lives in Tokyo and a quick preview of Seoul. Shin-Ōkubo is a vibrant symbol of Korean culture, fostering a lively community for K-lovers. In fact, Shin-Ōkubo, along with its reputation as a popular tourist attraction, also stands as a vivid intersection of Korean identity and Japanese society, where history, commerce, and culture converge to create a uniquely dynamic area for both immigrants and enthusiasts alike.

Followed by the Pacific War in 1945, Japan was left in severe social and economic destitution. Intense bombing raids devastated major cities, including Tokyo. Shin-Ōkubo, located within Tokyo’s Shinjuku ward, was not an exception to those left heavily damaged. Lacking financial aid from the government during the nation’s intense focus on postwar recovery, Shin-Ōkubo was left as one of Tokyo’s poorest neighborhoods. Its low land value and neglected infrastructure made it one of the few affordable places for people with limited means. Eventually, amid the postwar chaos, Shin-Ōkubo served as a refuge for migrant day workers and returning soldiers who opened small instrument repair shops. The district’s reputation as a place for the economically displaced was forged in the 1940s.

By 1950, Japan’s first Korean factory, the Lotte Confectionery Factory, was built in Shin-Ōkubo. This enterprise attracted a wave of Korean workers who congregated in the district. As a result, worker dormitories were built, and the district gradually developed into a hub for Korean day laborers. Around 1983, as years of tense Japan-South Korean relations began to ease up, the Japanese government began to encourage student exchange programs with South Korea to foster mutual historical understanding.

Gradually, Shin-Ōkubo came to represent the hub of Korean migrants and the Korean culture that they brought in. Over these decades, Shinjuku’s popularity spilled into Shin-Ōkubo, creating a fertile ground for small businesses, particularly for Korean-owned shops and restaurants. The popularity of the neighborhood, particularly shaped by Korean culture, grew even more in the 2000s following a major surge in Korean TV dramas across Japan. As Korean pop culture became increasingly entrenched in the lives of Japanese audiences, Shin-Ōkubo’s Koreatown began promoting itself as a gateway to Korea—a place where the Japanese could experience the sights, flavors, and trends of Seoul without leaving Tokyo. This cultural boom transformed the area into the Shin-Ōkubo we know today: a cultural hub for the young bloods seeking authentic Korean products and cuisine.

“[Shin-Ōkubo] used to be a dark and melancholic street, but now it has become multicultural,” recalls Aijin, a Korean barber who now works in Shin-Ōkubo after moving to Japan in 2022, emphasizing the drastic transformation of the street over time. For Aijin, the launch of his barbershop in K-town marked the realization of a long-held dream—one that allowed him to craft unique hairstyles for a diverse clientele. The rise of Korean pop culture played a pivotal role in his success, attracting customers eager to replicate the looks of popular K-pop idols. This influx of clients from various backgrounds helped Aijin refine his skills, enabling him to adapt his skills to different hair types and styles.

Aijin’s story reflects a broader trend in Shin-Ōkubo, where Korean-owned small businesses continue to flourish alongside the growing popularity of Korean culture. Today, the district in the heart of Tokyo is comprehensively packed with authentic cultural dishes and cuisines, as well as K-pop merchandise and cosmetic products. Visitors are welcomed by a wide range of products featuring new popular brands directly imported, as the K-beauty and K-food industry continues to boom. Supermarkets in Shin-Ōkubo are almost exact replicas of markets in Korea, offering cultural dishes and ingredients that are typically only available in South Korea. They offer a mix of diverse commodities, from traditional seasonings and side dishes to manufactured drinks, instant noodles, and frozen foods.

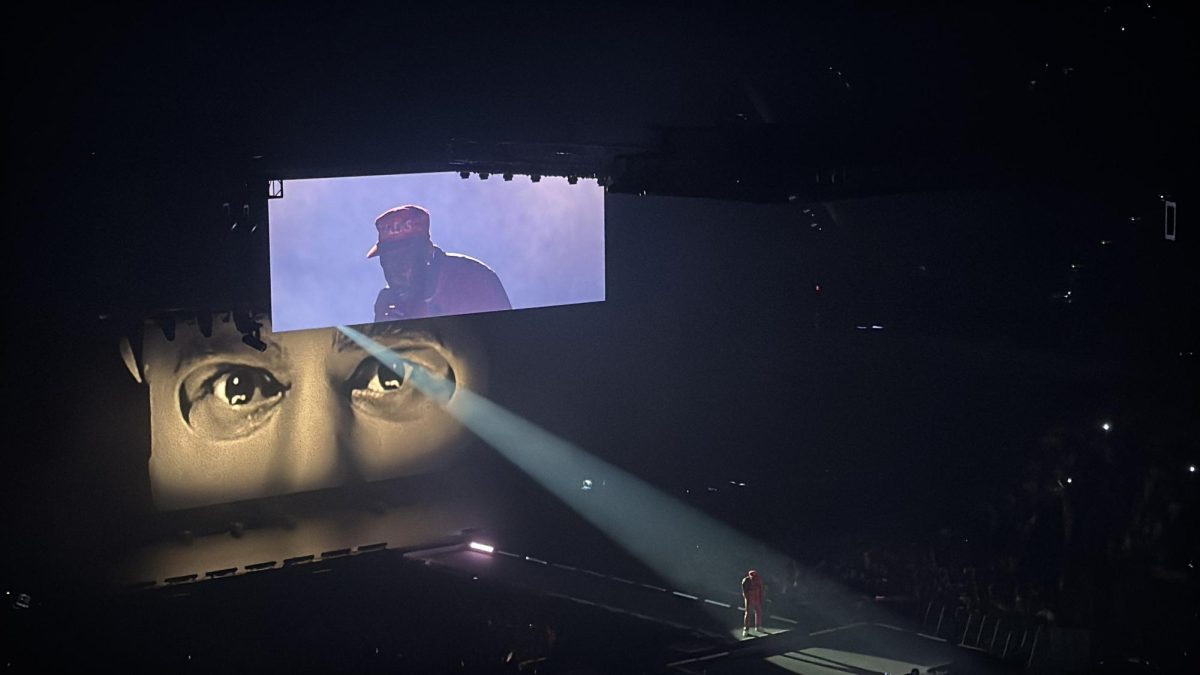

A few steps onwards along the same road, stores lined up offering K-pop merchandise, featuring everything from albums and photo books to posters and autographed merchandise of well-known groups like BTS, BLACKPINK, Stray Kids, ENHYPEN, and NewJeans. These idols dominate the market and shape the district’s dynamic atmosphere, drawing visitors from all around Japan. K-pop’s impact goes beyond merchandise; it fosters a deep cultural connection as fans recreate idol looks and trends, making Shin-Ōkubo a place full of spirit and aspirations. Such unique products, rarely found anywhere else in Japan, have created a wave of popularity both among Korean immigrants and local Tokyoites. Korean immigrants are drawn by a sense of nostalgia and familiarity from their hometown, while Japanese consumers flock to experience the vibrant trends of K-culture firsthand, without having to travel hours and miles away.

Image credit: Jimin S (’27)

Although K-town is most famous for its colorful storefronts offering trendy products, Shin-Ōkubo also plays a vital role in the lives of Korean residents who seek ease in communication and cultural familiarity. Gyuri K. (’27), a student at Sacred Heart, has lived in Japan since 2019, when her parents were transferred from Korea to Japan for work. Gyuri shares her first experience in K-town when she visited the place for a dentist appointment. “Even though my parents speak Japanese, their Japanese is not good enough to the level where they can talk to a doctor about professional health advice. So we prefer visiting a Korean doctor whom we can communicate comfortably with.” Now, as her first visit was three years ago, Gyuri’s visits to K-town extend beyond practicality. “I feel safe [when I visit K-town]. The nostalgia kicks in,” she admits, reflecting on the emotional comfort she finds in the familiar atmosphere of home. The nostalgic cultural dishes in Shin-Ōkubo play a large role in fostering a sense of home. Gyuri explains, “Now, whenever I visit K-town, I eat, I eat, I eat. One more thing, I shop there because I can easily encounter Korean snacks and ingredients there that I can bring home with me.

Unlike Gyuri, who turns to Shin-Ōkubo for a sense of home, Ana I. (‘27), a Romanian student who relocated to Japan in 2020, visits the neighborhood to explore a culture that’s new to her. Drawn by the influence of K-pop and Korean beauty trends online, Ana finds K-town to be the most accessible place in Tokyo to shop for authentic Korean skincare. “It’s technically easier to get Korean products by going to Koreatown. I don’t know how much I trust the Amazon products online, so it’s more practical to go to Koreatown and experience the product before actually purchasing it.” In a market where imported goods can often feel unreliable or overpriced, like Ana, many foreigners find Shin-Ōkubo as a reliable retail place that offers a blend of convenience and credibility.

Further on, Ana’s trips have extended beyond practical shopping. Her visits have grown into opportunities to engage with Korean food and culture on a deeper level. “I don’t just go there for the Korean products, but I also go there to eat some of the street food, especially because my family likes Korean food,” she shares. “It’s really been a cultural experience.” Now, Shin-Ōkubo has become a place for cultural immersion where Korean culture can be previewed hands-on conveniently.

Despite Shin-Ōkubo thriving as a commercial hotspot, not all impressions of the neighborhood are uniformly positive. Some praise the enclave for convenient cultural exchange, while others offer more skeptical takes. Gyuri, despite finding comfort in its familiarity, also admits, “It can feel a bit sketchy. I wouldn’t go there at night by myself.” Common concerns about the area regard overcrowding, aggressive street vendors, and the occasional lack of cleanliness that leaves parts of the district feeling unsanitary and disorganized. Likewise, Ana notes that while K-town markets itself as a window into Korean culture, it doesn’t fully capture Korea’s full depth. “There are a lot of K-pop stores, but my one problem is that they only sell products of the big groups. Since it’s called Koreatown, I expected to have everything,” she explains. “If I went to a Japanese music shop, I wouldn’t expect it to have the products of less popular groups, but in Koreatown, I expected to have a wider range.” Her disappointment underscores the hidden truth: as commercialized as Shin-Ōkubo may seem, the enclave remains a mere stylized version of Korean culture shaped by market trends, rather than a comprehensive reflection of Korea itself. Such limitations, however, don’t directly diminish the neighborhood’s appeal. Instead, such factors reveal room for growth to better meet the expectations of its diverse audience.

From an unknown, desolate street to a thriving center representing the Korean Wave, Shin-Ōkubo’s Korean town has reshaped how such foreign culture is perceived, experienced, and celebrated in Japan. It is now a vibrant spot full of Korean merchandise, Korean food, and beauty products that attract Korean immigrants, K-pop fans, and shoppers seeking authentic Korean goods. As Korean culture continues to boom, so will Koreatown, becoming more dynamic and active than ever before.